A FEW OTHER EVENTS FOR

FEBRUARY 10:

- Happy birthday E. L. Konigsburg (From the Mixed-Up Files of Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler, The View From Saturday), Stephen Gammell (The Relatives Came), Mark Teague (How do Dinosaurs Say Goodnight?), James Rice (Cowboy Night Before Christmas), and Lucy Cousins (Maisy series).

- It’s the birth date of Charles Lamb (1775–1834) Tales from Shakespeare.

- The Postal Telegraph Company of New York City introduces the singing telegram in 1933.

- In 1996, the IBM supercomputer Deep Blue defeats Garry Kasparov in chess. Read Way Down Deep in the Deep Blue Sea by Jan Peck, illustrated by Valeria Petrone.

- Children of Alcoholics Week begins today. Read The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian by Sherman Alexie.

February has been designated Black History Month since 1976, and this observance has allowed for both the acquisition and publishing of many fine children’s and young adult books. But although there are so many stories from Black American history to be told, these books often focus on the same subject areas or heroes.

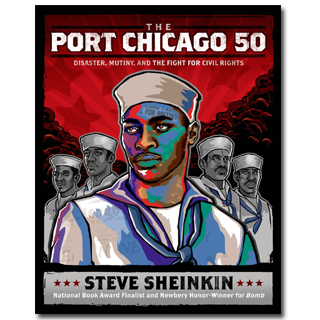

Hence I welcome the unique story that appears in Steve Sheinkin’s The Port Chicago 50: Disaster, Mutiny and the Fight for Civil Rights. The author of Bomb and The Notorious Benedict Arnold, Steve focuses his new book on the American Navy in World War II, and particularly on the black servicemen stationed at California’s Port Chicago. He opens this account with a chilling quote: “At some time, every Negro in the armed services asks himself what he is getting for the supreme sacrifice he is called upon to make.”

The book begins with the story of Pearl Harbor, not the usual rendition, but one that takes place on the USS West Virginia. There, Dorie Miller, an African-American heavyweight boxing champion, grabs the anti-aircraft machine gun of a dead man and fires away at the Japanese airplanes. For his efforts that day he will be given the Navy Cross for “distinguished devotion to duty.” But he will go back to his duties as a mess attendant, cooking and cleaning laundry for the white servicemen on the ship because “It was the only position open to black men in the United States Navy.”

With his usual craft and skill, Sheinkin has set out his theme and subject matter in one dramatic chapter. He then takes readers quickly through the history of blacks fighting in American wars and begins his exploration of the conditions for black servicemen in World War II. Readers are introduced to those training for the navy, who must struggle against patterns of discrimination well worn and accepted. Eventually a group of these men get assigned to Port Chicago, California, where they load bombs on American ships. This task, not assigned to white sailors, is carried out with less than ideal attention to the men’s safety.

Then one day, an explosion kills three hundred sailors, and others refuse to load these bombs until their grievances are heard. Thurgood Marshall, who later became the first black justice of the Supreme Court, takes up the case. Sheinkin manages to relate courtroom drama in The Port Chicago 50 as skillfully as Harper Lee did in To Kill a Mockingbird.

In book after book, Steve Sheinkin has redefined nonfiction for children—showing how great stories and great research can be combined to give children books they will savor. The Port Chicago 50 takes a story little known to both adults and children and brings it to life. It reminds us just how far our country has come—and how far it still needs to go.

Here’s a passage from The Port Chicago 50:

The white officers at Port Chicago had been given a brief course on the safe handling of bombs and ammunition. They’d also spent a few hours at ports on San Francisco Bay, watching professional stevedores at work loading ships. That was the extent of their training.

It was more than the black sailors got.

The Navy never even gave the men any kind of written manual describing how to handle bombs safely. No such manual existed. Some safety regulations were post on sheets of paper at the pier, but not in the barracks, where the men might actually have time to read them; the officers didn’t think the black sailors would be able to understand written regulations.

Originally posted February 10, 2014. Updated for 2024.

Quite the book this was. I read Sheinkin’s book for a course last fall, and I held on to my copy. The book shares a refreshing and worthwhile perspective on the U.S.’s history during World War II, and the Port Chicago 50 incident demands to be heard.

Here’s to hoping for more equally revealing books!